‘Kenya ni home’. A declaration. A frankly bemusing, if often faintly ridiculous, argument about authorship and ownership. 2024? 2021? 2011 (the oldest claim I have seen so far?) A lack of realisation that its provenance goes further back. To 1997. To 1963. To two thousand years ago.

‘Kenya ni home’. A claim to citizenship. The grabbing of a birthright, with all the benefits that accrue. ‘I am a Kenyan’, this proclamation says, and therefore I grant myself the entire gift of what Kenya owes her children. What I have I wasn’t given – it was born in me and of me. I need not prove anything, nor do I need anyone’s permission, to be Kenyan, any less than I need to prove anything to claim the comfort of my mother’s hearth. ‘Kenya ni home’. ‘Mimi ni mKenya’.

‘Daima mimi mKenya, mwananchi mzalendo’. Eric Wainaina, 1997. My pride is justified by the wondrous deeds of my countrymen. Their deeds are to be admired on the world’s stage, and I arrogate to myself the right to say – as you admire them, there goes I. But at the same time, it makes me strive that little bit harder: I must also do the thing that makes my countrymen proud of me.

‘Daima mimi mKenya’. An anthem. A song of comfort when evil men bomb our people on a Friday morning. When, all weekend, Rose calls out from deep in the bowels of a bombed-out building, her cries growing fainter the closer the rescuers get to her. Her cries stopping forever just as the rescuer’s hands reach hers. ‘Daima mimi mKenya’. Helping us shed tears as one nation.

‘Mimi ni mKenya’. ‘Ich bin ein Berliner’. John F. Kennedy, 1963. The statement of a big brother, here to face off with a menacing bully. To reach beleaguered Berliners, the Soviet tormentor will have to go through thisBerliner, the most powerful of them all. A rallying declaration of reassurance for citizens of a besieged city. Berlin, a lonely outpost in the middle of the menace of Soviet domination, needing the most powerful man in the world to declare ‘I am one of you’. The citizens of the city, especially of the western part which has for many months stared at a wall, barbed wire, dogs, searchlights, and watchtowers, manned by soldiers whose orders are to kill anyone who has designs to cross over from the east. ‘Ich bin ein Berliner’. ‘Mimi ni mKenya’.

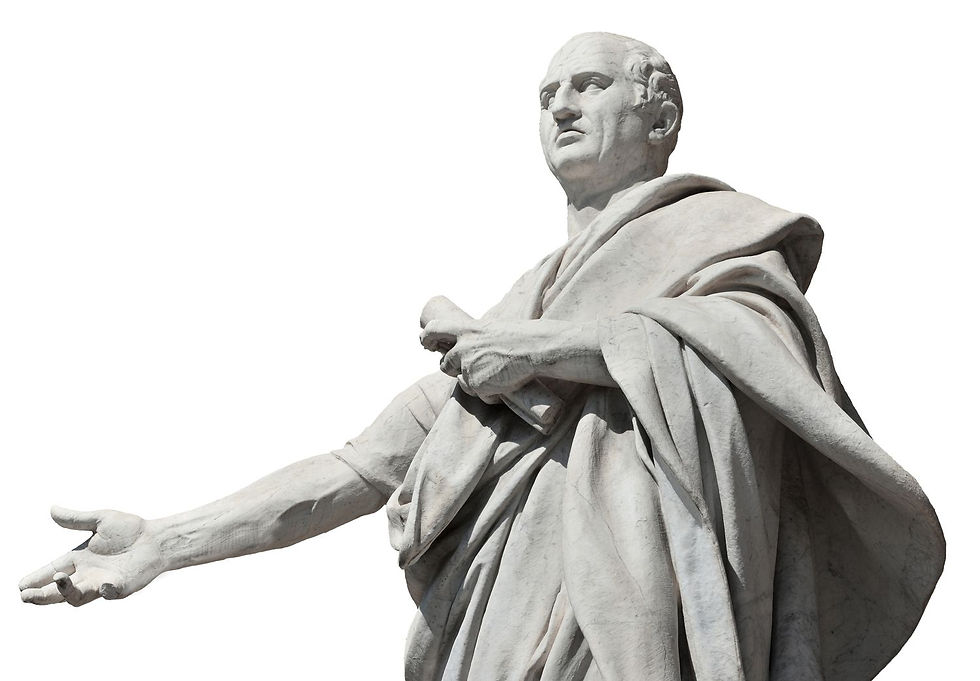

‘Mimi ni mKenya’. ‘Ich bin ein Berliner’. ‘Civis Romanus Sum’ St Paul of Tarsus, 57AD. Being a citizen of the Roman empire confers one enormous advantages. The most important one is in extremis. ‘Civis Romanus sum’. I am a Roman citizen. I cannot be executed. Crucifixion is reserved for the heathens from the provinces. Jesus Christ, citizen of Judea, can be crucified. Paul, citizen of Rome, cannot (‘Is it lawful for you to scourge a man that is a Roman, and uncondemned?’, asks Paul. The centurion, much afraid, tells his commander: ‘Take heed what thou doest, for this man is a Roman.’ Paul is asked ‘Tell me, art thou a Roman?’ Yes, Paul replies. And my citizenship was not purchased, ‘I was free born’. And the Roman captain is much afraid, ‘after he knew he was Roman, and because he had bound him’. The Acts of the Apostles, chapter 22.

‘Civis Romanus sum’. A spoken amulet. The ultimate protection against the caprice of an ancient empire.

‘Civis Romanus sum’. Marcus Tullius Cicero, 70 BC. It works, until it doesn’t. Cicero tells, In Verrem, of the corruption of Gaius Verres. The Roman governor of the province of Sicily. Verres, who tortures and crucifies Publius Gavius, despite Gavius’ ever more desperate cries of ‘Civis Romanus sum’. Cicero declares at the trial of Verres: ‘Then he orders the man to be most violently scourged on all sides. In the middle of the forum of Messana a Roman citizen, O judges, was beaten with rods; while in the mean time no groan was heard, no other expression was heard from that wretched man, amid all his pain, and between the sound of the blows, except these words, “I am a citizen of Rome.” He fancied that by this one statement of his citizenship he could ward off all blows, and remove all torture from his person. He not only did not succeed in averting by his entreaties the violence of the rods, but as he kept on repeating his entreaties and the assertion of his citizenship, a cross--a cross I say--was got ready for that miserable man, who had never witnessed such a stretch of power’. Mary Beard tells us that as a final humiliation, Verres crucifies Gavius, with the cross facing in the direction of Rome. ‘Utado?’

Civis Romanus sum. Ich bin ein Berliner. Daima mimi mKenya. Kenya ni home.

Comments